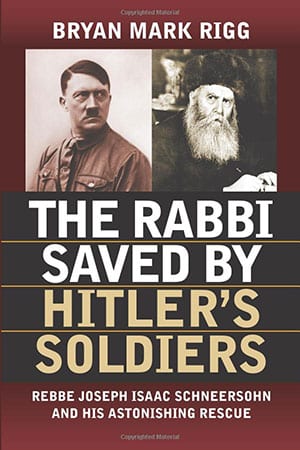

Hitler's Jewish Soldiers

The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military

On the murderous road to “racial purity” Hitler encountered unexpected detours, largely due to his own crazed views and inconsistent policies regarding Jewish identity. After centuries of Jewish assimilation and intermarriage in German society, he discovered that eliminating Jews from the rest of the population was more difficult than he’d anticipated. As Bryan Rigg shows in this provocative new study, nowhere was that heinous process more fraught with contradiction and confusion than in the German military.

Contrary to conventional views, Rigg reveals that a startlingly large number of German military men were classified by the Nazis as Jews or “partial-Jews” (Mischlinge), in the wake of racial laws first enacted in the mid-1930s. Rigg demonstrates that the actual number was much higher than previously thought-perhaps as many as 150,000 men, including decorated veterans and high-ranking officers, even generals and admirals.

As Rigg fully documents for the first time, a great many of these men did not even consider themselves Jewish and had embraced the military as a way of life and as devoted patriots eager to serve a revived German nation. In turn, they had been embraced by the Wehrmacht, which prior to Hitler had given little thought to the “race” of these men but which was now forced to look deeply into the ancestry of its soldiers.

The process of investigation and removal, however, was marred by a highly inconsistent application of Nazi law. Numerous “exemptions” were made in order to allow a soldier to stay within the ranks or to spare a soldier’s parent, spouse, or other relative from incarceration or far worse. (Hitler’s own signature can be found on many of these “exemption” orders.) But as the war dragged on, Nazi politics came to trump military logic, even in the face of the Wehrmacht’s growing manpower needs, closing legal loopholes and making it virtually impossible for these soldiers to escape the fate of millions of other victims of the Third Reich.

Based on a deep and wide-ranging research in archival and secondary sources, as well as extensive interviews with more than four hundred Mischlinge and their relatives, Rigg’s study breaks truly new ground in a crowded field and shows from yet another angle the extremely flawed, dishonest, demeaning, and tragic essence of Hitler’s rule.

ISBN-10: 0700613587

ISBN-13: 978-0700613588

In warfare, it is understood that there are three levels of conflict: Strategic, Operational, and Tactical.

The Strategic Level normally involves decisions that are made at the highest levels. During World War II, this was best exemplified by Roosevelt’s, Churchill’s, and Stalin’s decision to prioritize victory in Europe over victory against Japan. In making such a decision, each leader was provided input by many. That input was not simply about number of forces available, amount of war fighting equipment available, logistics available, etc. It also included other important factors including ongoing suffering of both combatants and non-combatants, focus and impact of the media, cultural and religious make-up of the enemy and other less measurable aspects. Taking these various metrics into consideration, in the simplest of terms, the European Theater became the focus of main effort and Asian Theater became an economy of force arena.

Once this Strategic Decision was made, the Operational Level of conflict came into focus. Because the fight against Japan was to be an economy of force arena and the number of forces, war fighting equipment and logistics would be limited, it was decided that the operational execution would be two pronged…a central drive under Admiral Nimitz and a southern drive under General MacArthur. Limited capability would be allocated depending on the priority of action decided upon by these two commanders.

Once again using the Pacific Theater, the Tactical Level can best be described by individual battles… the Battle for Iwo Jima being a perfect example. Here it was the individual Marine, Sailor, and Airman combining to impose their will on a tenacious enemy. It was a titanic struggle. The acts of individual heroism and selfless sacrifice were a 24/7 occurrence for friend and foe alike.

In the book you are about to read, “Flamethrower”, the author does a brilliant job of connecting all three levels of conflict and their impact on each other. You cannot understand the tenacity, the fanaticism, and the savagery of the Japanese soldier without understanding their culture, the impact of religion, and the deep-seated value system of the Samurai. All of these are best seen in the person of General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the architect and Commanding General of the Defense of Iwo Jima.

Likewise, the bravery of the Marines and Sailors who assaulted across the black sand beaches of Iwo Jima, fought through the mine fields and the interlocking bands of fire from hidden pillboxes and bunkers, who endured constant artillery and mortar fire, and finally secured the island is hard to understand without knowledge of what esprit and brotherhood means to Marines. All of this is best seen in the person of young Corporal Hershel Woodrow “Woody” Williams.

In the case of both General Kuribayashi and Corporal Williams, as with every combatant on the island, neither was a saint nor a sinner. Each had their own flaws that have been masterfully researched and documented by the author. In reviewing the history of General Kuribayashi, we learn that he commanded troops during the China campaign and his troops carried out brutal acts of rape, beheadings, and torture. In reviewing some of the claims made by Corporal Williams, questions about the acts that resulted in the awarding of his Medal of Honor are raised. Additionally, the approval process that resulted in his receiving the award are brought into question. But in each instance, these flaws and questions were counterbalanced by documented acts of bravery and selflessness, by their devotion to their fellow warriors, to their Country, and to their countrymen and women. We must not allow these flaws or questions to totally obscure all they did on that Island.

At the end of the day, the focus of the reader will be inextricably drawn to the island of Iwo Jima itself and the battle that took place there from 19 February-26 March, 1945. It was a horrific battle. During the 36-day campaign to take the island, a Marine fell to Japanese fire every two minutes…every two minutes for 36 days. Over 26,000 Americans were killed or wounded on Iwo Jima. It was the only battle in the history of the Marine Corps where Marines suffered more casualties than the enemy. Having been to the island on four occasions, I can attest to the fact that it still bears the scars of that titanic struggle. It is a place heavy with history and long on memories. It remains a haunting place.

Iwo Jima provides the stage for this remarkable book. It is on this stage that numerous actors play out their roles. Although the author draws on his prodigious research to help us understand many of the actors, it is on the stage itself where those actors are truly revealed as they face the horrors of close combat. Like a chess game, the leaders at all levels, on both sides, must think several moves ahead. Executing those moves are individuals who are asked to do the nearly impossible. Whether, like the defenders, fighting from pillboxes and caves with little water, food, or supplies and knowing that their lives are forfeit or, like the attackers, enduring withering fire, massive casualties, and measuring success by the number or yards cleared in a day, you will know and understand the true meaning of sacrifice. As you read this book, hopefully you will come to believe that the words engraved on the granite base of the Marine Corps War Memorial at the Arlington National Cemetery might not only be intended to honor Martines, but to recognize all who fought on that island, for in truth: “Uncommon Valor Was A Common Virtue.”

Charles C. Krulak

General, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret.)

31st Commandant of the Marine Corps

December 2019

I met Bryan Mark Rigg, then a USMC 2 nd Lieutenant at The Basic School, back in 2001. He had unfortunately had an injury and was transitioning to a teaching job at American Military University where I served as a board member. I encouraged the young officer in the new life he had and that he should take pride that, although his military career was cut short, he still had earned the title Marine. In the last 19 years, he has written several books on WWII and recently, with Flamethrower, he has turned his attention to the Marine Corps during that iconic struggle. He has returned home, so to speak, by giving back to the organization which has shaped his identity.

Rigg has written an extremely detailed and superbly researched book about some of our WWII great battles like Iwo Jima and documented some of our incredibly superb Marine Warriors who brought victory against Japan. Using never-before-seen documents, he actually tells us many new facts about Guam and Iwo Jima and the men who fought there that will hopefully educate the next generation of historians and Marines.

In Flamethrower, Rigg has focused on two men in particular, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi (the IJA Iwo Jima commander) and Medal of Honor recipient Woody Williams. And then, in general, he has focused on countless Marines whose stories until now have remained unknown and who all prove my motto: “Every Marine is, first and foremost, a rifleman. All other conditions are secondary.” Analyzing documents in archives throughout the U.S., in Europe and Asia, Rigg has tied together short biographies of numerous American heroes to tell the larger story of the Pacific War. And in exploring these documents, Rigg has found many controversies, especially about Kuribayashi (a mass-murderer) and the war-hero Woody Williams himself, a man I have had the privileged to meet several times and who I find to be rather humble and a good representative for the Medal of Honor Society. When encountering these controversies though, instead of shying away from them or burying them (which some encouraged him to do), Rigg, like a true Marine and thorough historian, faced them head on.

Medals throughout time rarely give the appropriate recognition to a warrior who puts his life on the line for his country and comrades. We know many Marines throughout the ages have not got the appropriate recognition they deserved. The majority of those who fought on Iwo who deserved a Silver Star or Navy Cross or Medal of Honor never did because the bureaucracy failed them or their officers had died or their witnesses had perished—in other words, there was no one to document their deeds. And in few cases, we also see the reverse that some people got recognized at a level that maybe they should not have been rewarded at. In Flamethrower, one will learn about the medal process from World War II like I have never seen. And in doing so, one will see that Woody’s Medal of Honor process was confusing and full of problems, some stemming from politics, and some stemming, unfortunately, from Woody himself. But we readers and even Woody, as a true Marine, should be able to handle the factual truths contained within this book. With this being said, we must realize anyone who fought on Iwo deserves respect for what he had to undergo to defeat the Japanese and bring victory to the Corps in the toughest battle Leathernecks have fought. And Rigg uses both Kuribayashi and Woody’s stories to bring to life commanders like Lieutenant General Graves B. Erskine and Captain Donald Beck so they can find their rightful place in history—Erskine especially has been ignored for too long.

Flamethrower also goes into the psychological and sociological background of the Japanese soldiers Marines faced. I have never read such a thoroughly investigated study about the enemy we encountered in the Pacific. When one understands who we fought and defeated, one just remains thankful for what our servicemen accomplished. Few truly understand how tenacious the average Japanese soldier was and how this enemy was the only one Marines have faced, especially at the war’s beginning, who really bloodied our noses and knocked us down. But we got up, as we always do, and fought again, and eventually we brought down the Japanese soldier with powerful riflemen who were better trained, equipped and motivated than their adversary.

In the end, you are about to read one of the best documented books about what warfare was like in the Pacific War against Hirohito’s Japanese forces. Flamethrower is a superb testimony to the efforts of our servicemen and leaders as they went about winning WWII to obtain the Victory over Japan or V-J Day.

Al Gray

29th Commandant of the United States Marine Corps (1987-1991)

December 2019

Flamethrower is an unusual book that doesn’t fall neatly into a typical genre. While Bryan Rigg started out to write a biography of the sole remaining surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the battle of Iwo Jima—Hershel ‘Woody’ Williams—his lens widened as he researched and wrote. He ultimately concluded: “Although Woody’s life is worthwhile to study, it is really useful in telling the larger story of the war and about the countless men who never returned home.” (p.787)

In the latter area, to a degree not seen in any other biography, Rigg digs into the stories of the Marines who fought alongside Williams at Guam and Iwo Jima. He mined the unique sources at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis for information on dozens of Marines whose names rarely grace the pages of battlefield narratives. He brings to life their deeds as told not only in medal citations, but with added details from supporting documents, biographical information, and photos of the individuals. His approach provides a more human dimension that even books based on oral history accounts don’t quite achieve. Equally significant, it brings to life many who died on the battlefield and thus go largely missing from a narrative based on the recollections of surviving veterans. His research in muster rolls also revealed that one Marine who had long been credited as a supporting participant in Williams’ actions was not even present that day, as he already had been evacuated for shell shock.

Juxtaposed with that focus on individuals is the author’s ‘larger story.’ It is not a standard account of the conflict at the strategic, operational, or tactical level, but instead a detailed look at Japanese atrocities in China and during the Pacific War—what he aptly refers to as “Japan’s Holocaust.” That information is hardly new, with various episodes having been well documented in books such as Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking. But it seldom appears in battle narratives beyond brief mentions of Japanese cruelty, and many military readers are likely not that familiar with the full story. Rigg drives home the totality and scale of the utter depravity of the Imperial Army and makes clear that this trait was ingrained in the very culture of the organization and pervasive in every locale and against everyone it encountered, civilian or military. Not only does that background lend added context to the bitter, no-quarters combat that characterized the Pacific War, it justly diminishes the stature of the Japanese commander on Iwo Jima. Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi has been widely recognized as the canny architect of the toughest defense the Marines faced in World War II, but he was hardly a noble warrior and his hands were as bloody as his contemporaries.

The author is well suited to the subjects he addresses. He served as a soldier in the Israeli Defense Forces and a Marine officer, and has degrees in history from Yale and Cambridge. The battle of Iwo Jima is well trod ground in military history, but Rigg is at his best in developing many previously unused sources and bringing to light fresh perspectives. In describing Williams’ experience becoming a Marine, the author unearthed previously unused materials on recruit training that provide good insight into the process of shaping young men to fight in the cauldron of the Pacific. In a similar fashion, he describes the development of flamethrower operations during World War II, looking at the technology of the weapon, experiments in the fuel mix, and the tactics honed to make it effective on the battlefield. The book is lavishly illustrated with photos, many of them never before published. Readers are cautioned that some of the images are gruesome depictions of Japanese barbarity, as well as battlefield casualties.

Finally, he provides unprecedented insight into the process of determining who received medals and the twists and turns that accompanied some awards (or non-awards). Williams’ Medal of Honor was not a foregone conclusion given the concern of senior Marine leaders about holes in the documentation, and there remain questions about exactly what he did that day on Iwo. But Rigg appropriately quotes Eugene Sledge: “Carrying tanks with about seventy pounds of flammable jellied gasoline through enemy fire over rugged terrain in hot weather to squirt flames into the mouth of a cave or pillbox was an assignment that few survived but all carried out with magnificent courage.” (p.150) Whether Williams destroyed seven Japanese fortifications or some lesser number, he definitely merited recognition for his deeds, as did many of his fellow Marines at Iwo. This book is a tribute to all those who endured so much to achieve victory over a terrible foe.

Jon T. Hoffman

Colonel

United States Marine Corps Reserve (Ret.)

[Rigg] brings to life [numerous Pacific War Marines’] deeds as told not only in medal citations, but with added details from supporting documents, biographical information, and photos of the individuals. His approach provides a more human dimension that even books based on oral history accounts don’t quite achieve…[Flamethrower also] drives home the totality and scale of the utter depravity of the Imperial Army and makes clear that this trait was ingrained in the very culture of the organization and pervasive in every locale and against everyone it encountered, civilian or military…[Rigg’s] book is a tribute to all those who endured so much to achieve victory over a terrible foe.”

Marine Corps Gazette

Spring 2020

Tremendous research. An incredible story of America at war filled with new first-time material. Fair on all accounts. I’ve studied Iwo Jima (not Iwo To) as a Marine for over 30 years. I’ve been there three times, and walked from the steep and foamy black sand beach to the top of Mt. Suribachi and into a cave. I participated in the 50th Anniversary of the landing with the USMC’s 31st MEU(Special Operations Capable). On the 50th, some of the survivors, on both sides, still wanted to fight. Others wanted to hug and cry. I am reading Bryan’s book for the third time now and it is as powerful the third time as the first. Rigg has done his profession and the Corps a great service standing tall to fairly and with aplomb tell the truth with credible references to support. Americans and indeed the Corps is strong enough to honor those that fought Imperial Japanese forces under unthinkable conditions and accept the facts of warriors, medals, and the WWII medal process. Rigg gives us lessons worth thinking about as American warriors and citizens.

—Dr. Edward M. “Ned” Hallowell, author, Driven to Distraction and Delivered from Distraction

—Susan Hauser, assistant dean, Yale University, 1973-1999